From Dream to Reality – The Making of Rubicon

YEAR: 2069

The conference room was abuzz, reporters from every corner of the globe, pressed into the stuffy room, awaiting the space agency chief. When he finally appeared, he took them through an elaborately detailed explanation of the mission to Mars.

“We launched three ships last year, carrying the heavy robotic equipment that began the excavation of the site. Rubicon is the vision of some of the brightest thinkers of our day. It will be brought into existence far below the surface of Mars, protected from harsh conditions and elements by the tons of rock and dirt above its domed atriums and long network of corridors.”

A flurry of questions and an hour later, the news agencies were reporting on the biggest story of the year. Choosing the site for the settlement had taken years of research by teams of explorers, seeking out the best location for a permanent home on Mars. The task was not simple. The settlement structures had to meet specific requirements that ensured the survival of the occupants.

“And on Mars, that is a tough ask. Stay tuned as we bring you more on the launch of the Rubicon mission to Mars after these messages,” a well-groomed news anchor concluded the segment that aired across the country the same night as the chief’s news conference.

Her notes were filled with Mars facts and information. She read through them again, preparing to go live when the commercials segment ended.

Besides the deadly, unbreathable atmosphere and much lower gravity, teams of building crews knew their biggest challenge was the probability of a direct meteorite hit. She worked on her script, refining the complex jargon into terms the viewers of her popular broadcast could digest.

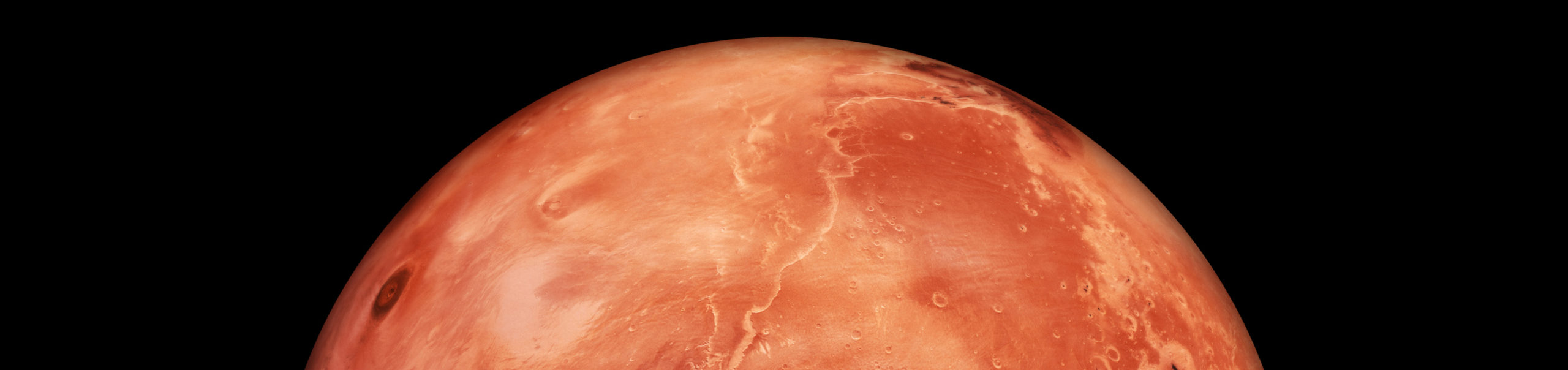

Mars is routinely pelted with space debris, which makes for deadly projectiles, unchecked by the thin atmosphere of the Red Planet. It’s unlike Earth, with its dense atmosphere that slows down projectiles, preventing many of them from entering as they “skim” off the cushion of air above our heads. Mars’s atmosphere does little to slow down or deflect the flying boulders, rocks and pebbles that rain down in random, deadly showers. A meteorite strike is a foregone conclusion. No structure proposed for a surface settlement is capable of repelling or surviving a strike that could instantly wreak havoc and cause death.

Yes, dramatizing the possibility of people dying out there would help add to the excitement of what was, really, just another space science lesson. Show them the stakes, she thought.

The news conference handout went on to explain that it stood to reason that the only way to guarantee the longevity and safety of the settlement was to search for a suitable cave complex in which to build it. The vast system of lava tube caves formed millions of years ago, deep below the Lunae Planum, was a find like no other. The site wasn’t ideally situated, but it would do. There was room for expansion and zones on the surface for landings and the necessary out-structures that would be the surface works of the complex far below.

As the show returned, her quick explanation handled most of the science with finesse. The producers then cut to some footage of the chief, himself, offering explanations about current timetables.

“The excavation is difficult. The regolith makes the robotic machines break down more than expected. It’s caused some delays in the completion of the project and means that budgets are strained. This has made it necessary to streamline or even rethink some of the more elaborate plans for Rubicon.” His face had a slight flush to it, indicating he was not comfortable talking about budget cuts and delays. It was unfortunate for him that it was an election year and his job was politically driven.

The clip of the chief’s presentation continued, edited for entertainment value by the news studio.

“The 3-D printers work day and night, producing everything from stairs to forks. The printers were a necessary expense and one, I feel, have been worth every cent and the extra effort to get them installed and operational.”

YEAR: 2071

Two years after the initial media frenzy had subsided and the buzz of a mission to establish a permanent settlement on the red planet had subsided, the crews that manned the Rubicon construction site on Mars were hard at work. They were tough and capable, smart and quick, coping with a seemingly endless array of problems and setbacks.

They worked in shifts lasting four months, heading back to Earth with the returning ships that had offloaded more equipment, electronics, substrates for the printers and a replacement crew. It was grueling work. The teams spent hours at a time in thick, clumsy life-support suits. It slowed them down some, but as the machines did most of the work, the human-caused delays did not impact the project timeline.

When the day came to switch on the power in the main control room, lights came on all through the underground settlement. Outside the lit biomes built into the deep caverns of the Lunae Planum, a faint glow revealed the surrounding areas, pushing back the shadows of the alien landscape into which Rubicon had been born.

Air began to circulate within the settlement’s underground structures. The hum of fans was loud at first, then eased off when a stable air pressure was achieved. Warmth began to make itself felt as the team members noticed their suits compensating for the changes in air temperature. Visors, fogged and dirty before, began to clear and smiles could be seen on all their weary faces. Then with a jarring force that knocked a few of them over, the graviton system, that had been powering up and developing stores of electro-magnetic energy, magnetized the floor panels to a near-Earth gravity level. The team felt heavy, their tools almost impossible to lift for the first hour after the system came online. When they slowly trudged back to the airlock system to decontaminate their suits and stow them for recharging, it was a difficult task that made many of them feel sick and exhausted.

It took the rest of the day for the team to get used to the graviton’s effects. Some faired better than others, but the adjustment was soon behind them.

“What a pleasure to walk through these clean corridors without those damn suits.” Captain Riley stretched up to touch the beige wall of the corridor he and Dr. Lin were walking through. The narrowness of many of the corridors had meant it was a challenge to maneuver the bulky suits without banging into conduits and bulkheads. Their smiles showed what a relief it was to finally be free of that bulk.

“It’s amazing to breathe fresh, circulating atmosphere, everywhere we go now, and not just in our crew pod.” Lin was in agreement. It had been a psychological burden on many of the crew. He’d been studying the effects of sensory deprivation on their moods and psyches for the past year. Spending hours in the suits had started to leave a marked impact on many of the crew members, who complained of depression and rising anxiety.

Heading down to the shiny, new and quiet canteen, they celebrated with a supply of bootleg liquor that had been smuggled aboard the supply ship that brought them to Mars almost three months ago.

“Cheers! To the team who got to throw the switch. I’m proud of all your hard work, people.” Riley raised his cup, his head already spinning from the effects of the alcohol. “Yes, there are weeks of eliminating bugs in the system ahead of us, but the power is on and there is atmosphere and gravity. Mission accomplished.” A shout of hurrahs went around the room. Twenty of them stood, toasting and slapping each other on the back. It was a merry evening with hangovers keeping most of them out of their suits the next day.

The explosion in the power transfer station the following week killed two of Riley’s team. He was devastated. It meant their celebrations were short-lived and premature. The accidental overload of the main circuit board blew one of the big fuses, the resulting explosion cutting all the power and setting the completion of the final stage back by many weeks. Riley knew it had been a mistake, and it cost him his commission. He and his team were replaced with haste and hush that minimized the media exposure of the deadly incident.

The next shift was made up of systems experts, botanists and genetic biologists. There were few among them that spent time fraternizing and the atmosphere of the new settlement took on a more serious tone as they raced towards their separate deadlines.

YEAR: 2075

“Water filtration is proving tricky. The system is constantly kicking back issues with the drill and suction of the ice crush from the glacier.” The new commander, Captain Edison, made his report to Mission Control back on Earth in January of 2075.

Rubicon was three years behind schedule, billions of dollars over budget and had cost the lives of thirteen crew members. The press conference in October that year was called by the new chief of the combined space agency programs that had taken over the immense burden of completing the Mars settlement. Alex Plith was unprepared for the pressure of the media’s persistent attempts to find fault with the troubled mission.

She stood before the throng of reporters who all looked a little more skeptical than they had when they had first been told about the amazing settlement being built on Earth’s distant neighbor. Too many overruns, too much politics and far too many deaths had shattered people’s illusions that settling Mars was going to be just another day on the job.

Ms. Plith cleared her throat in the tense silence of the room, looking out over the sea of unfriendly faces. “Work has been officially completed on the construction project.”

“It’s 2075. Rubicon was slated to open its doors in 2072. What is the Administration’s response to allegations of corruption and misuse of funds?” a reporter fired from the back of the room.

She pressed on, ignoring the failures of what she believed was an incredible achievement. “All that is left to do is for the first harvest from the massive greenhouse complex to be brought in, and that will be the responsibility of the elite crew that will be Rubicon’s first permanent settlers. Two hundred people have been chosen, each with their own assignments. As it is still a military outpost, each was selected from the ranks of serving personnel in the Alliance’s coalition forces.”

There were a few more questions, mostly from science media outlets. For the most part, the completion of Rubicon was met with ambivalence and resignation. It had been a disaster of a project and people were just glad it was over. Many returned to their lives and forgot all about the colony now permanently ensconced in the brand new, state-of-the-art facility on Mars. They had lost interest in the greatest achievement of their age. It meant little to them that there were humans living and making a future for themselves on another planet.

They didn’t give a second thought to what that new home was like: cold, hostile and deadly.